acquired July 11, 2001

download large image (1 MB, JPEG, 2205x1655)

acquired July 11, 2001

download GeoTIFF file (7 MB, TIFF)

acquired July 11, 2001

download Google Earth file (KML)

In August 1768, Captain James Cook,

naturalist Joseph Banks, and a shipload of sailors set sail from England

to Tahiti to observe the Transit of Venus. Camped out on Point Venus, they witnessed the event on June 3, 1769. Cook sketched the transit, but Banks had surprisingly little to say about it. Perhaps he was distracted by the wonders of the island itself.

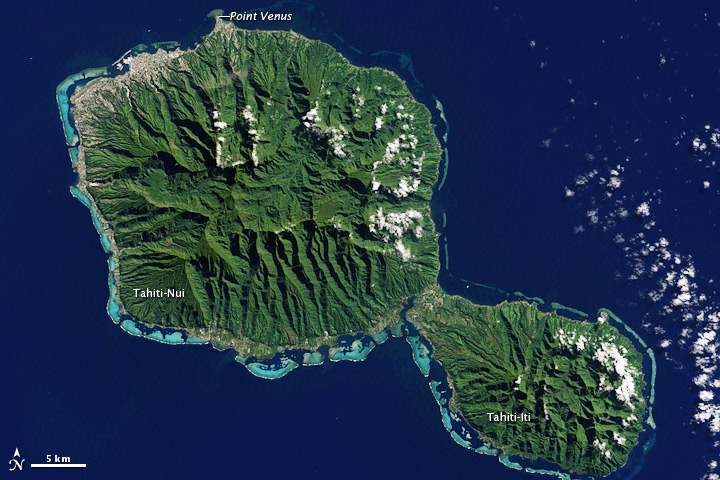

The Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus on the Landsat 7 satellite captured this natural-color image of Tahiti on July 11, 2001. This island is part of a volcanic chain formed by the northwestward movement of the Pacific Plate over a fixed hotspot. Tahiti consists of two old volcanoes—Tahiti-Nui in the northwest and Tahiti-Iti in the southeast—linked by an isthmus.

Through studies of its rock layers, geologists have figured out the likely history of Tahiti-Nui. Today it is roughly round, and it was roughly round when it first formed as a volcanic shield between 1.4 million and 870,000 years ago. But between then and now, it had a different contour. Both the northern and southern flanks of Tahiti-Nui collapsed sometime around 860,000 years ago, gouging massive arcs out of the island’s perimeter. Soon after the northern flank collapse, a second shield volcano began forming. Volcanic material on the northern side of Tahiti-Nui eventually overtopped the original volcanic structure and started filling in the southern depression.

Although Tahiti-Nui now has a fairly symmetrical contour, it has an asymmetrical three-dimensional shape. Mountains are taller on the northern half of the island.

Yet something else besides volcanic activity has shaped Tahiti: rain. Heavy tropical rains have carved deep valleys, some with nearly vertical walls up to 1,000 meters (3,000 feet) tall. The angled sunlight in this image brightens some slopes, while leaving others in shadow. Tahiti’s sharp relief has complicated the geological surveys because they cause so much erosion. But the same rains have also promoted the growth of the lush plants that carpet both Tahiti-Nui and Tahiti-Iti.

Though the Transit of Venus was the stated objective of the British expedition, Banks was likely more interested in Tahiti’s plants. Specimens he collected from Tahiti, New Zealand, South America, Australia, and Java accounted for roughly 1,300 new species, and his famed collected is now stored at the Natural History Museum in London.

Complementing the rich life on land is marine life around Tahiti’s perimeter. Coral reefs fringe the island, and the reefs are thickest on the southern and western sides. Reefs frequently form along the submerged slopes of volcanic islands.

The Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus on the Landsat 7 satellite captured this natural-color image of Tahiti on July 11, 2001. This island is part of a volcanic chain formed by the northwestward movement of the Pacific Plate over a fixed hotspot. Tahiti consists of two old volcanoes—Tahiti-Nui in the northwest and Tahiti-Iti in the southeast—linked by an isthmus.

Through studies of its rock layers, geologists have figured out the likely history of Tahiti-Nui. Today it is roughly round, and it was roughly round when it first formed as a volcanic shield between 1.4 million and 870,000 years ago. But between then and now, it had a different contour. Both the northern and southern flanks of Tahiti-Nui collapsed sometime around 860,000 years ago, gouging massive arcs out of the island’s perimeter. Soon after the northern flank collapse, a second shield volcano began forming. Volcanic material on the northern side of Tahiti-Nui eventually overtopped the original volcanic structure and started filling in the southern depression.

Although Tahiti-Nui now has a fairly symmetrical contour, it has an asymmetrical three-dimensional shape. Mountains are taller on the northern half of the island.

Yet something else besides volcanic activity has shaped Tahiti: rain. Heavy tropical rains have carved deep valleys, some with nearly vertical walls up to 1,000 meters (3,000 feet) tall. The angled sunlight in this image brightens some slopes, while leaving others in shadow. Tahiti’s sharp relief has complicated the geological surveys because they cause so much erosion. But the same rains have also promoted the growth of the lush plants that carpet both Tahiti-Nui and Tahiti-Iti.

Though the Transit of Venus was the stated objective of the British expedition, Banks was likely more interested in Tahiti’s plants. Specimens he collected from Tahiti, New Zealand, South America, Australia, and Java accounted for roughly 1,300 new species, and his famed collected is now stored at the Natural History Museum in London.

Complementing the rich life on land is marine life around Tahiti’s perimeter. Coral reefs fringe the island, and the reefs are thickest on the southern and western sides. Reefs frequently form along the submerged slopes of volcanic islands.

Related Resources

- Hildenbrand, A., Gillot, P.-Y., Bonneville, A. (2006) Offshore evidence for a huge landslide of the northern flank of Tahiti-Nui (French Polynesia). Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 7(3), Q03006.

- Hildenbrand, A., Gillot, P.-Y., Le Roy, I. (2004) Volcano-tectonic and geochemical evolution of an oceanic intra-plate volcano: Tahiti-Nui (French Polynesia). Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 217, 349–365.

- Hildenbrand, A., Gillot, P.-Y., Marlin, C. (2008) Geomorphological study of long-term erosion on a tropical volcanic ocean island: Tahiti-Nui (French Polynesia). Geomorphology, 93, 460–481.

- Natural History Museum, London. (2012) Sir Joseph Banks. Accessed June 7, 2012.

- Phillips. T. (2012, June 2) James Cook and the Transit of Venus. Science@NASA. Accessed June 7, 2012.

Links

- Viewing the Transit of Venus from Space. NASA Earth Observatory.

- Cook’s View of the Transit of Venus. NASA Earth Observatory.

- Island Evolution, Part 1: Pitcairn Island. NASA Earth Observatory.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Caption by Michon Scott.

- Instrument:

- Landsat 7 - ETM+

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario